A 1971 article from The New York Times entitled “Knell for Irish Bars Echoes in Brooklyn” recites a litany of closings, including Emerald Isle, Moriarity’s, Downey’s and Callahan’s, the latter of which was “replaced by the Mill, a restaurant featuring watermelon cordials and organically grown vegetables.” The piece chalks the shift up, at least partially, to “ethnic turnover.” (It turns out that the gentrification we bemoan today wasn’t all that different 50 years ago.) A more recent spate of articles posits that the city’s Irish bars appear to be, once again, in peril.

A new age is perpetually dawning, surfacing fears that an older, more dignified era is disappearing. A few times a year, we must necessarily perform our lamentation for New York’s vanishing institutions. We wring our hands and profess an entire generation of establishments to be on their collective deathbed, victims of socioeconomic violence, casualties of skyrocketing rents and shifting trends. This isn’t untrue—not for any of the city’s bars or restaurants; it’s the cutthroat nature of an industry that requires deep pockets to gain a foothold, and operates upon razor-thin margins with very little room for trial and error or misstep, much less fickle tastes.

In the last decade, every bar in the Blarney Stone chain, except a single decrepit outpost in the Financial District, has shuttered; in the 1970s they flourished, numbering 34 at one time. In 2016, SoHo’s beloved Puck Fair went dark, as did Dempsey’s in the East Village. Last year saw the closing of St. Dymphna’s, Dorian Gray, McAleer’s, and Langan’s. It’s certainly true that Irish bars are dying off in greater numbers, as old-school business models built on the appeal of cheap beer and homey food can’t support increasing overhead costs. But the notion that Irish bars as a category are endangered is simply not true—there are still well over a hundred operating in Manhattan alone, and dozens more in Brooklyn and Queens. This recent series of casualties is, in some ways, a reminder that the Irish bar lives on in iterations ancient, new and existential. You just have to know where to look.

The Irish Are Coming

New York City’s drinking culture has been shaped by Irish pubs since Irish immigrants began flooding its shores, first in the 1820s and again during the Great Famine in the 1840s. (My mother’s own family, famine refugees, arrived to America during this time, albeit through Chicago, another great custodian of stateside Irish bars.) Between 1820 and 1930, over 4.5 million Irish arrived to America, making up nearly a quarter of New York’s population. Soon after, Irish-run saloons abounded, acting as gathering places and civic centers, places to find jobs, post mail, hold public meetings and gather news of relatives back “on the old sod,” all while drinking ale.

McSorley’s (which claims establishment in 1854, but is likely closer to 1862) is as close as you can still get to this kind of Tammany Hall-era watering hole. With its sawdust-scattered floors, obsolete beer taps and coal-burning oven, the bar’s uncanny stasis telegraphs the rough-hewn texture of another century, its rooms haunted with memories and traditions of a people seeking solace in drink and community. For this reason, it’s become a sort of spiritual touchstone for the Irish pub outside of Ireland. Ask any Irish bar owner or tender in New York which other Irish bars they frequent and McSorley’s is the single resounding answer.

Other vestiges of that era remain scattered across Manhattan. Across town is the regal Landmark Tavern, opened in 1868 by Patrick Henry Carley on what is now 11th Avenue, in Hell’s Kitchen. Technically a waterfront tavern at the time it was built, Landmark catered to a clientele of Irish longshoremen and merchants. At Chelsea’s Peter McManus Cafe, established in 1936 and today run by fourth-generation owner Justin McManus, the setting is equal parts polished tavern and old-fashioned haunt, complete with burnished wood paneling, Tiffany windows and a proper burger platter. P.J. Clarke’s on 3rd Avenue, which has operated as a bar since 1884, was acquired by Irish immigrant Patrick “Paddy” J. Clarke in 1912. Its tin ceilings, penny tile floors and carved rail describe a specific progression toward the neighborhood corner bar, a classic style that’s since seen a cycle of recession and swell over the last century. (The company now operates P.J. Clarke’s properties across the country, built with the same bar-centered blueprint.)

If you define the Irish bar by these few remnants of a bygone New York, you would find that, unequivocally, yes, the Irish pub is all but dead. But if you define it not just as a collection of iconography, ephemera and ale but a living, breathing space that purveys a certain kind of hospitality and atmosphere, then you know that the Irish pub has been reincarnated over and over again.

Guinness and Potato Skins

Two weeks before St. Patrick’s Day the second floor of The Playwright in Times Square is decked out with glittery green hats and feathered green boas dangling from the ceilings. A few minutes before the lunch rush, Top 40 plays while several people drink beers, heads tilted back to gaze at the four or five television screens above the bar downstairs. Within a couple of minutes, three people with Irish accents have appeared. A fourth, owner Frank Dwyer, sits down with a cup of coffee. “A little old lady walking by named the bar for us,” he says, explaining the pub’s namesake and its proximity to the Theater District. Dwyer, 66, came to New York in 1972 as a contractor and carpenter, and bought his first bar in 1995. He’s opened ten others since, including McGee’s, Jack Demsey’s, Legends, McHale’s and two more Playwrights.

Following World War II, Irish arrivals to the U.S. slowed until 1986, when American immigration laws shifted and a younger generation of Irish began to flock. In Irish neighborhoods, like Washington Heights, Woodlawn, Yonkers and Sunnyside, Irish bars manifested in quieter, less pronounced ways, catering to neighborhood regulars—people who knew the bar was Irish because they were, too. Pubs like The Playwright on the other hand, centered amid business and tourist corridors, declared Irishness as a selling point—a universal symbol of hospitality and cold beer. “People love to hear the brogue,” says Dwyer.

Maggie’s Place, a true neighborhood bar, in what no longer qualifies as a neighborhood (47th Street between 5th Avenue and Madison), touts its Irishness, but without the clovers. A holdover from Midtown of a different time, the place was opened in 1974 by Teddy and Maggie Whelan who arrived to America via the first transatlantic Aer Lingus flight and the SS America, respectively; they both worked at Jim Downey’s bar at the Irish Pavilion at the 1964 World’s Fair. Their son, Martin Whelan, took over the bar with his brother in 1992, making aesthetic changes and menu updates that were in line with tradition, but that also reflected the changing tastes of the city around it. Today, it feels as if it has more in common with a proper American tavern. But Whelan also co-owns 12 other bars, including the 16,000-square-foot Stout on West 33rd Street, which has supersized the idea of an Irish sports pub. Even if it’s had to shape shift to remain relevant—add more televisions, Buffalo wings, potato skins and craft beers—the rowdy, clover-laden Irish bar of the late-20th century persists because it champions so much of what America today holds dear: sports, fried food, cold beer and television.

In many ways, these bars codified what much of America considers to be the quintessential Irish pub: A rowdy sports bar mashed up with the warmth and congeniality of Irish tradition, served with a well-pulled pint of Guinness and, perhaps, a shepherd’s pie. But their malleability is also proof that the most enduring aspect of the Irish pub transcends décor and pints; it’s about lineage and etiquette—and something far more ethereal.

The Pub Abides

If a natural descendent to McSorley’s exists it would be Swift Hibernian Lounge. A cavernous space just off of the Bowery, Swift was opened in 1995 by Irish immigrants Danny McDonald and Mike Jewell. It’s since served as a way station for their newly arrived countrymen. “You feel the soul and this history as soon as you walk in,” says Mike O’Sullivan, the Kerry-born co-owner of two new Irish pubs, Grace’s in Chelsea and Hartley’s in Clinton Hill.

In some ways, at its opening, Swift marked a reimagining of the Irish-American bar—one that consciously cultivated an atmosphere apart from the Irish sports pubs of Midtown. A dark, warm bar with nary a television to be found, its Irishness is of an older, more literary tradition, not unlike McSorley’s which hosted everyone from journalist Joseph Mitchell to poet E.E. Cummings. Named for Jonathan Swift, a 17th-century Irish writer, the bar often hosts live Celtic music and readings, and its drink list can compete with any new concept that crops up around it. Currently, the bill of fare includes a draft Penicillin, a Bramble and a Beaujolais by the glass. McDonald and Jewell also own the now-classic Ulysses Folk House and the waterfront megaplex Pier A with Dubliner Anthony Malone.

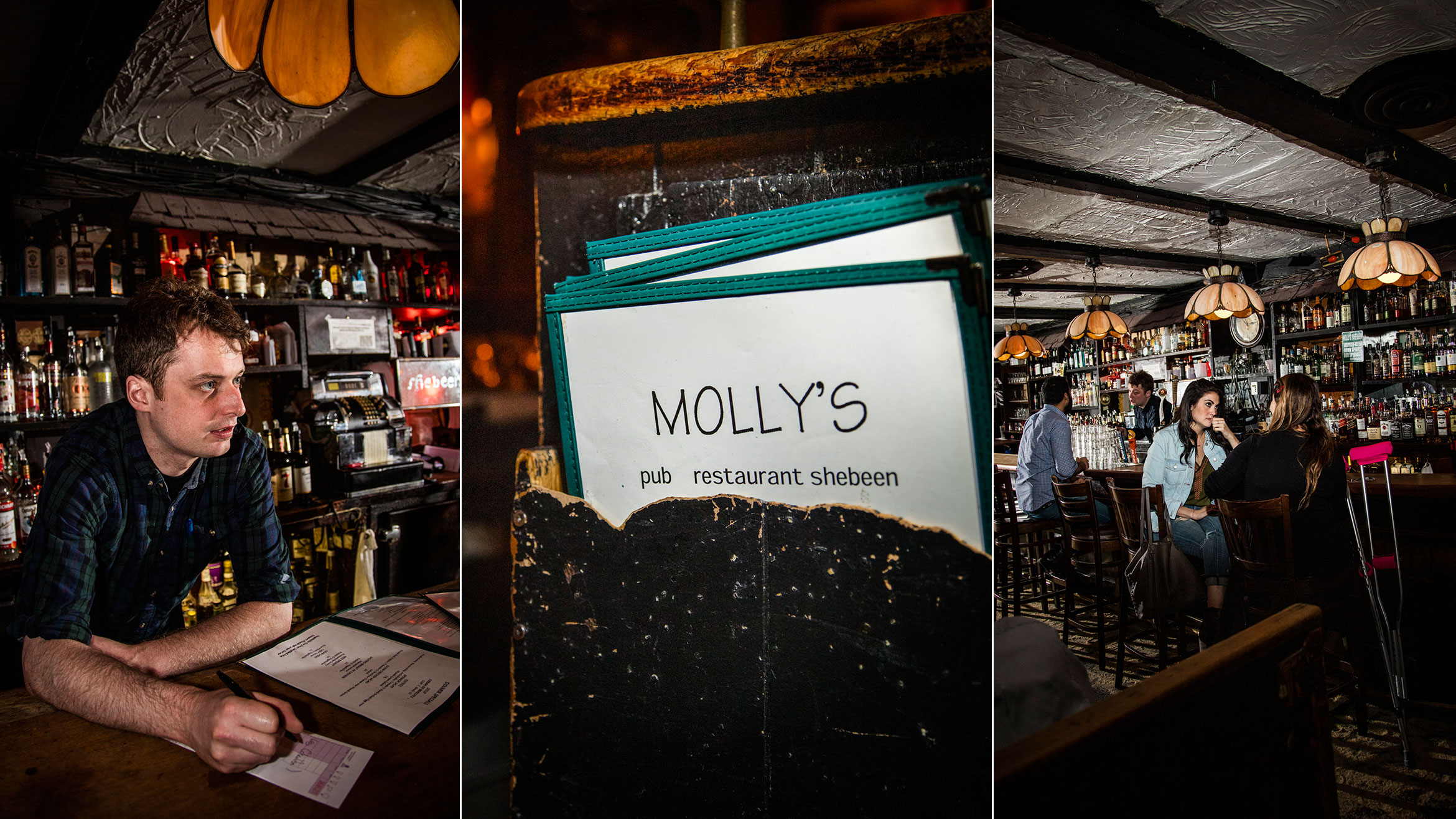

It’s possible to situate Swift as the leader of a legion of bars that began to pop up, mostly downtown, in the mid- to late-1990s. A New York Times piece written in 1998 proposes the new breed arose as a “contrapuntal to the rowdy shot-and-a-beer Irish bar.” Still-chugging establishments like Arlene’s Grocery, The Scratcher and Rocky Sullivan’s are included in this charge. Tom and Jerry’s, Sláinte and the reimagining of Molly’s Shebeen also fit into this moment.

The Celtic Tiger, a period of economic growth in Ireland that began in the mid-1990s and ended in the late aughts, helped bridge this wave of scrappy, low-key pubs with a more conceptual style that cropped up in the early 2000s. “I was able to go to my bank and they lent me a serious chunk of money to open a bar in New York,” says Ruairi Curtin, co-owner of seven venues in the city. That first loan went toward building Bua on St. Marks, which Curtin opened with Mark Gibson and David Mohally in 2004. “At the time, a lot of bars had a TV, and we didn’t want one because we wanted conversation. We didn’t like the mainstream beers, so we got craft beers.” The spirit of Bua, they decided, should mirror the spirit of Ireland’s most classic, centuries-old establishments.

This idea, combined with a few good cocktails and a handful of excellent food items (engineered by Joaquin Baca, then of Momofuku), forged a semi-elevated neighborhood bar—something that was fairly revolutionary at the time. Next came Wilfie & Nell, Sweet Afton in Astoria, The Wren, The Penrose, The Bonnie and, most recently, The Spaniard. At all of these places, you may often find an Irish person behind the bar, but the only real hints of their owners’ origins are a handful of menu items (sausage and mash, Guinness always, lots of Irish whiskey) and the bars’ namesakes, all of which nod to Irish culture in one way or another.

The most notable newcomer to the Irish bar scene was Jack McGarry and Sean Muldoon’s The Dead Rabbit in 2013. (Danny McDonald is also a partner.) The interior—sawdust floors, Five Points iconography, snug booths—is meant to evoke the meeting point of sepia-toned New York and old-school Ireland, but updated to compete upon a global stage—and it did. The Dead Rabbit won World’s Best Bar in 2016. The result is a simulacra of the Irish pub, cast through a lens of nostalgia, landing somewhere between a movie set and an old-timey grog shop.

These days though, the latest breed of Irish bar often does not announce itself quite so loudly. But if you really look, Irish bars are everywhere. The Late Late, James Morrissey’s Lower East Side living room lounge, nods to its heritage via name only (a reference to Ireland’s boundary-pushing late-night show). At his club, The VNYL, known for Drake and Chance the Rapper sightings, a wall of Irish celebrities’ portraits—Phil Lynott, Sinéad O’Connor, Bono—provides another subtle allusion. Hartley’s in Clinton Hill, Grace’s in Chelsea, Factory 380 in Kips Bay, Elder Greene in Greenpoint, The Craic in Williamsburg and The Gray Mare in the East Village are all Irish-owned. However, apart from Irish staff and unflagging hospitality, you wouldn’t necessarily have occasion to note it.

Malone of Swift and Pier A attributes this consistent quality of kindness and openness to ancient Irish tribal laws that enforced hospitality as a core tenet of culture: “It’s been wired into our DNA for hundreds, thousands of years,” he says.

“There’s now a kick back to the simplicity of hospitality,” says Mike O’Sullivan (of Hartley’s and Grace’s). “There’s a big push to go back to what’s worked for centuries. Pubs are meant to serve everyone from docker to doctor. At home, all the old bars in Ireland, it’s just four walls. It’s what goes on inside the bar that matters.”

When an Irish bar closes, perhaps the effect is amplified because the idea of them has been woven into the city’s fabric for so long, that to eradicate it would be to kill off a vital bit of our city’s culture. In some ways, in the great swirl of cultural melding, the Irish pub has lent bits of its genetic material to spaces that don’t identify as Irish at all.

Which is why, if every Irish bar in New York closed, the idea of them would endure, threaded into beloved neighborhood institutions everywhere—the places we seek when we pull up a stool and push a few dollars forward in exchange for a chat and a cold one. Like any great myth, with each retelling, each reincarnation, the Irish bar simply sublimates to a kind of immortality. Now, it’s not just a place, but a story—an old friend, really—held within the collective subconscious as another version of home.